Is the manner in which the genders are differently employed and remunerated objectionable? Some say that so long as men and women choose their jobs, the resulting gender employment difference is unobjectionable. Kristi Olson1, however, offers a counterargument against the choice-based defence of the gender employment difference, based on two key claims. She argues that 1) Mere choice does not vindicate the gender earnings difference, if the option set from which women and men choose is objectionable, and 2) The current option set is, or may be, objectionable, specifically through state intervention through licensing laws. As a result of these claims, she argues that it is premature to claim that the gender employment difference is unobjectionable. In this essay, I argue that Olson misidentifies the choice-based argument for the vindication of the gender employment difference, and subsequently claim 1) is trivially true. However, I refute her argument for claim 2), instead arguing that licensing does not lead to the option set being objectionable. I go on to explore two other ways in which the option set may be objectionable, though argue this falls to the critic of a gender employment difference to demonstrate.

This essay is separated into three sections. In the first section, I lay out Olson’s argument. In the second section, I assess the validity of her first claim, arguing that Olson has misidentified the form of the choice-based defence of the gender employment difference, in that nobody argues that mere choice vindicates the outcome from an objectionable option set, but rather that given an unobjectionable option set, choice is a preference-maximising mechanism. As such, the argument shifts to whether or not the option set is objectionable, and in the third section, I examine whether we should accept Olson’s second claim that it may be. I look at three candidates for how the relevant option set for the gender employment difference may be objectionable: 1) Olson’s own example of licensing laws, 2) State intervention, and 3) The market. I argue that Olson’s example of licensing laws fails, due to the specificities of the microeconomics of licensing and that furthermore, whilst an objectionable option set may arise through either state intervention or the market, we need it to fulfil a specific set of criteria and this falls to the critic of a gender employment difference to demonstrate.

A Note on Diction

This essay focuses on the ‘gender employment difference’ instead of the more usual diction of the ‘gender wage gap’. I see issues with both ‘gap’ and “wage’. The issue with using the diction “gap” is that it promotes normative conclusions, which, in an essay on the objectionality of such differences seems pre-emptive and question-begging. The issue with “wage” is that it promotes the narrative of two workers, identical in every way but gender, doing the exact same work, for the exact same time, achieving the exact same results, and yet one receiving a $1.00 at the end of the day, and the other receiving only 77c. This, however, is not an accurate picture. A more accurate picture is that women and men are differently employed2.

What are the facts of the matter? If we are going to go with some version of the above story, we ought to control for occupation, and hours worked. However, if we look at the median hourly cash rate per occupation, the Australian Bureau of Statistics lists the difference as 8.4%3. Already, the purported difference has significantly lessened. Furthermore, if we control, through remuneration data aggregates such as US site Payscale, for parent status, job-seeking status, remote work status, education, age, race, job level, industry, occupation, and location, the median hourly gender earnings difference is found to be only 1%4. Similar results are echoed in a study of US male and female Uber drivers, in which, though initially reporting an hourly gender earnings difference of 7%, found that by accounting for experience, location and average driving speed, were able to entirely account for the difference, down to 05. This is to say that gender itself appears to exhibit a very small, between 0 - 8.4%6 impact on actual hourly wage, and that this effect diminishes the more we continue to isolate it as a variable.

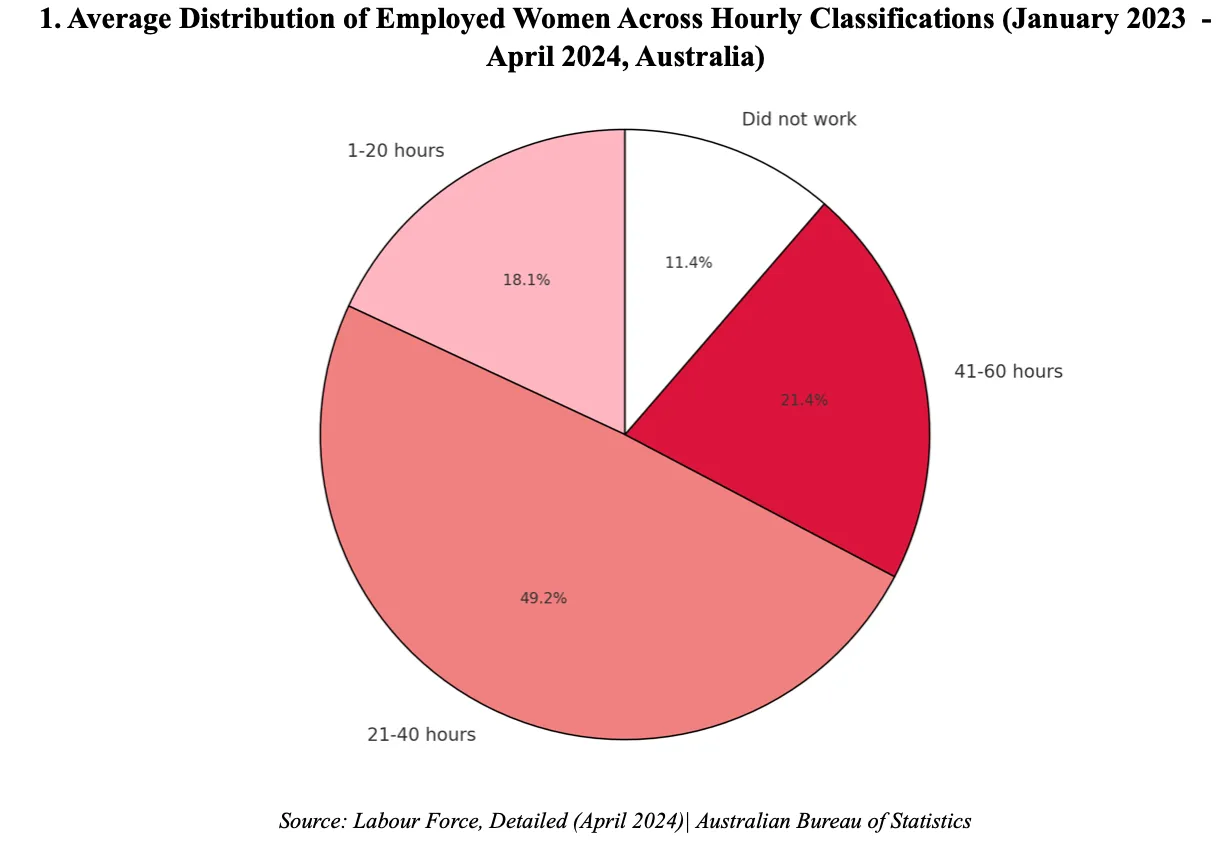

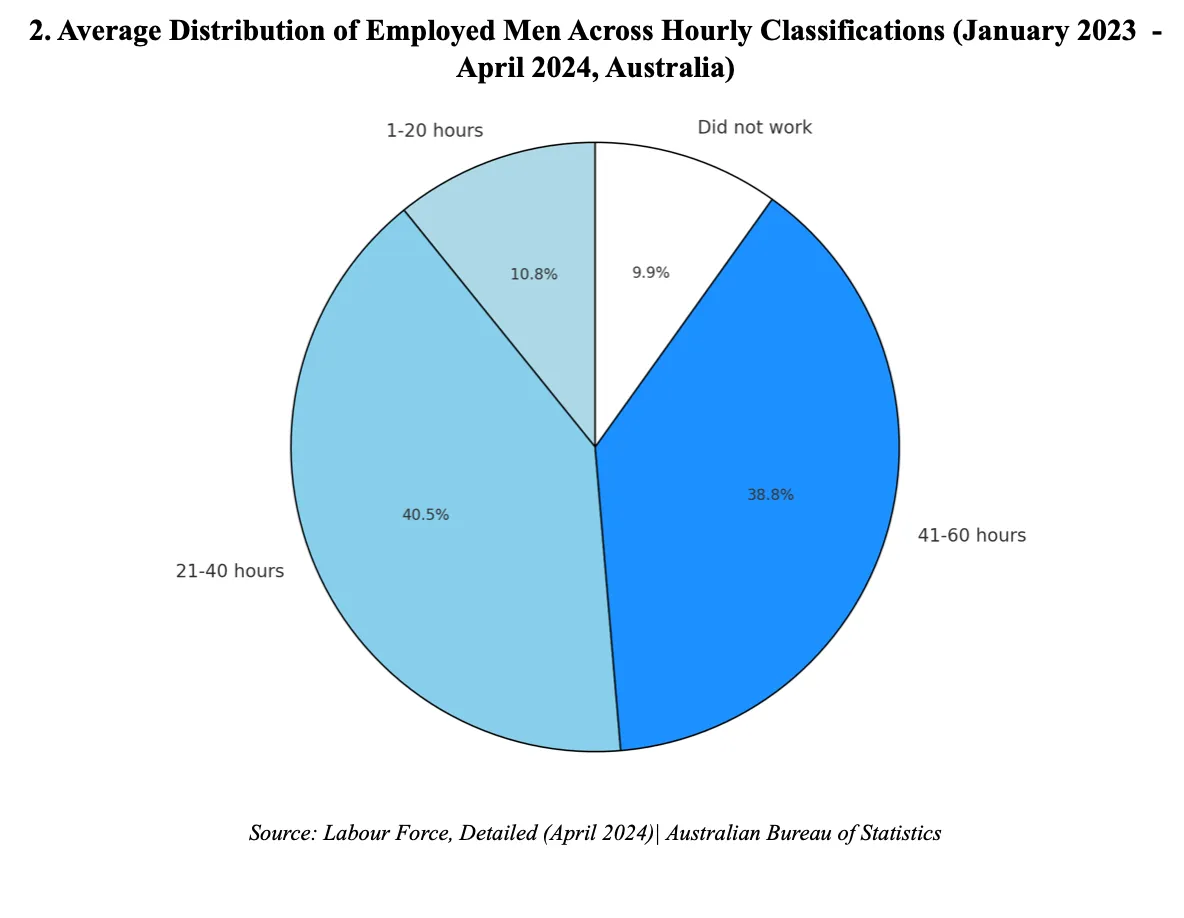

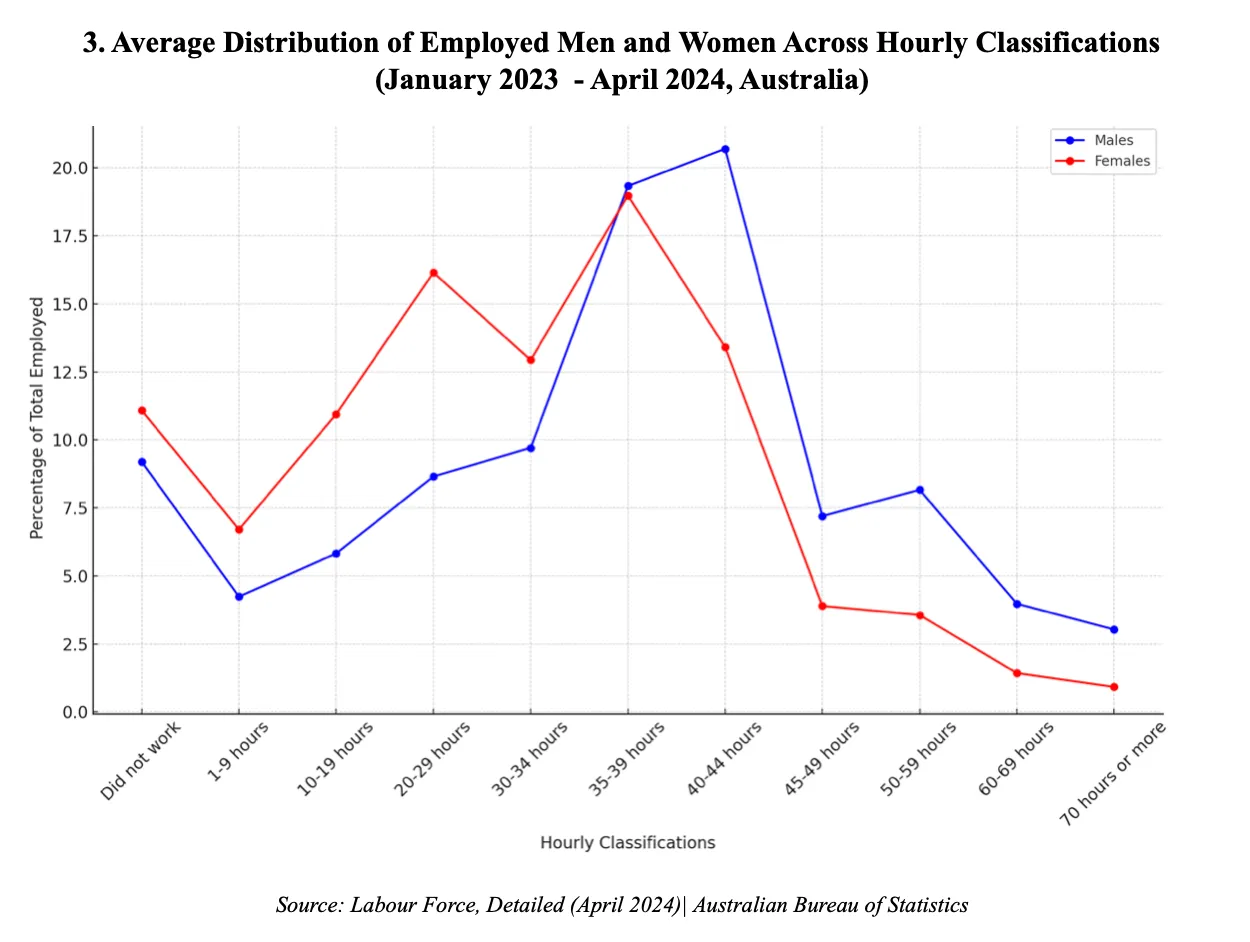

And yet, it is also true that across the board, in Australia, men make more per week than women, by a median average of 25.1%7. How can this be the case? The explanation may lie in the fact that the average hours, risk, flexibility, and overtime hours of employment between men and women vary. Below are three graphs included to align the reader’s intuitions regarding one of the starkest observed employment differences, the ‘weekly employed hours’ difference.

Similar differences are present regarding risk8, occupational sectors9, and overtime10. This is to say that men and women are differently employed. The fact that when we start accounting for variables, we are able to significantly, if not totally reduce the observed remuneration difference, points to this not being accurately described as a wage difference, but rather, an employment difference, construed of the very previously accounted for variables. Equally, and importantly, this does not refute the existence of discrimination, which may occur at any of the barriers to the mentioned variables through mechanisms such as promotions, overtime requests, and societal expectations regarding appropriate jobs and hours.

1. Average Distribution of Employed Women

2. Average Distribution of Employed Men

3 . Average Distribution of Employed Men and Women

Although Olson’s paper focuses specifically on remuneration, all the arguments will neatly translate onto any seemingly objectionable employment difference, and are not specific in regards to remuneration. We might just as validly ask, “Does choice vindicate the gender disparity in hours worked/overtime/risk of bodily harm?”. As such, in this essay, I will focus on the impact of choice on the objectionality of the gender employment difference, which appears to me to be the broader issue.

1. Olson’s Case

Olson purports to take an unusual tack against those who argue that men and women choosing their jobs vindicates and renders unobjectionable the gender employment and remuneration differences. Though many, she argues, dispute this by refuting the empirical claim: ‘That women and men’s occupations and remuneration are the result of choice’ she instead refutes the normative claim: ‘That choice renders the resulting difference unobjectionable*’11.* She argues instead that 1) Choice does not render the resulting gender remuneration difference unobjectionable, if the relevant option set is objectionable and 2) The relevant option set, being the occupations women and men choose from, indeed may be objectionable, through the state’s interference with licensing laws. As such, she argues, the defender of the choice-based vindication of the gender employment difference must either refute the normative claim 1), or refute the empirical claim 2) by demonstrating that the option set from which men and women choose cannot be objectionable in the ways she describes.

In order to address the strongest version of the choice-based vindication account, Olson makes three concessions for the sake of the argument, setting them to one side12. They are:

That the gender employment and remuneration differences are actually attributable to choice.

That the choices reflect genuine preferences, and are not the result of gendered socialisation.

That men and women face identical option sets.

Even if all these were true, though Olson thinks we have good reason to think they are not, she argues it still does not follow that the gender remuneration difference is unobjectionable13. In this essay, I too will set these arguments aside, and set my contention at the same level as Olson.

Olson then argues for her first claim; that mere choice does not render an outcome unobjectionable if the the relevant option set is objectionable. She argues this by appealing to two key cases: Executor and Shift Workers.

In Executor14, we are to imagine two nieces, Lourdes and Marissa, and an executor, who is dividing some assets [a painting, an armchair and $100,000] between them. Furthermore, for sentimental reasons, Lourdes favours the painting, and Marissa favours the armchair, so much so that either of them will choose any bundle offered by the executor that includes their preferred item. Following this, we are to imagine that the executor decides to offer two bundles: [the armchair and $1,000] or [the painting and $99,000] before allowing Marissa to choose, claiming that because she has the legitimate choice of either bundle, she has no recourse to complain. Marissa, given her attachment to the armchair, chooses the first bundle. Olson compares this to the concessions she made earlier, and argues that this is an example of a choice made from genuine preferences, when both parties have an identical option set, and yet, the outcome is objectionable in the form that “the bundles themselves are unfair”15.

Equally, in Shift Workers16 we are to imagine two employees, Nina and Bob, who do exactly the same work and are equally productive. Both Nina and Bob derive extra utility from working particular shifts because their friends also work those shifts, though Nina’s friends work on Tuesday, and Bob’s on Wednesday. Their boss, then, for no reason other than that he arbitrarily favours Bob, decides to give Nina the choice of:

A) Working the Tuesday shift (with her friends) for $8 per hour

or

B) Working the Wednesday shift with (none of her friends) for $10 per hour.

When Nina complains that the work they do is identical, her boss retorts that because she has been given a choice of shift, she has no legitimate reason to complain. Given that in this situation, it is true that Nina has mere choice, and yet the outcome remains objectionable, Olson argues that this demonstrates that mere choice does not render an outcome unobjectionable, if the option sets are objectionable.

Olson then argues for her second claim, that the current actual option sets faced by men and women may be objectionable, and that it falls to the defender of a gender employment difference to prove that they are not. In order to do this, Olson puts forth, one who argues that choice does vindicate a gender employment difference must provide three claims. Firstly, they must provide a normative account of when option sets are and are not objectionable17, secondly, they must provide a meta-account of why we should accept this account, and thirdly, they must empirically demonstrate that the option sets relevant to the gender employment difference match the details of their account18.

Furthermore, she argues, no matter which account of acceptable option sets is endorsed, if the government has enacted laws and legislation which affects the variable of interest (in Olson’s case, remuneration), then it is highly likely that this will fail any account of acceptability, and will be objectionable. Such interference could be justified, through appeal to democratic processes (though we would have to prove no outside interference) or greater utility (though this would have to be demonstrated). Furthermore, she argues, that in the case of a remuneration increase as a ‘free lunch’ benefit of legislation, it is still not justified to allow the benefactors to receive the increased remuneration, and this may be fixed by either taxing the benefactors, equally legislating other occupations, or by compensating the non-benefiting parties19. She does, however, argue that these should be distinguished from a Rawlsian justification, in which higher wages are not a fringe benefit or ‘free-lunch’ but rather necessary in order to induce supply.

Finally, Olson argues that we may have good reason to think that the government has influenced remuneration through legislation by affecting the supply and demand of female-majority and male-majority occupations, through licensing laws20, thereby making the option set objectionable, and therefore falling to the defender of a gender employment difference to demonstrate that this is not the case. Olson points to the ability of licensing laws to raise the wages of occupations such as dentists, the majority of whom are male, by restricting supply, whilst lowering the demand and therefore wages for occupations such as nurse practitioners, by restricting their ability to legally prescribe drugs and therefore demand, the majority of whom are women. Olson’s main point is that it is possible that “the regulatory regime as a whole”21 has effectively favoured male-majority over female-majority occupations, artificially inflating the remuneration of male-preferred occupations through ‘free-lunch’ legislation. While she concedes that there is only anecdotal support for this notion, she argues that until it can be demonstrated that this is not the case, it is “premature”22 to argue that the option sets are not objectionable, and therefore premature to say that choice vindicates the gender employment difference. Olson therefore argues that we may have good reason to believe that the current option set, and therefore its outcome, is objectionable, and that it falls on the defender of a gender employment difference to demonstrate that this is not so.

2.1 The Problem With Olson’s First Claim

The problem I see with Olson’s first claim, that ‘mere choice does not render an outcome unobjectionable, if the option set is objectionable’, is precisely that there is no problem. By this, I mean that the claim appears to be exceedingly obvious. To see this we need only consider a hyperbolic version of one of Olson’s cases, that of trademark-adjacent super-spy James Blond, who is captured by his nemesis Oldfinger and offered a choice of death by either laser or shark-tank. Does anyone think that the mere fact that Blond is permitted to choose the manner of his death renders the outcome unobjectionable? I think not. And so, how can it be that such a premise is the basis of the choice-based vindication argument? I put forth that it is not, and that Olson has misidentified the basis of the choice-based argument she responds to.

Choice, I argue, is not a ‘golden ticket’ of unobjectionality, but is a mechanism for maximising utility within a particular enforced option set. It allows the chooser to decide on the option that represents the highest expected utility and therefore functions to ensure the highest utility distribution of a given option set. This does not mean that an outcome involving choice will be unobjectionable, after all, in the James Blond case, the option set enforced by Oldfinger overdetermines that he will die, though the introduction of choice does make it less objectionable in that he may choose the method he prefers. We might agree that whilst it was objectionable of Oldfinger to condemn Blond to death, it was at least counterfactually utility-maximising of him to offer Blond the choice of preferred method, compared to choosing for him.

Furthermore, choice functions to vindicate apparent external inequalities between those who choose different options, by appealing to a sense of internal equality, or equality of preference-satisfaction, by allowing the choosers to decide on their optimal split23. In this sense, it is akin to restaurant-goers being asked to say “When.” regarding the amount of parmesan cheese on their pasta. Though there may be a final inequality in the amount of cheese by weight on plate, this is unobjectionable in the fact that it represents the utility-maximising split tailored to each individual’s preference.

The proper integration of choice, then, into a choice-based vindication argument for a gender employment difference is that if the option set is unobjectionable, and people have been allowed to choose their occupations based on their genuine preferences (which Olson concedes), then the resulting allocation of occupations represents the optimal utility-maximising split, according to the revealed preferences of the choosers, and is therefore unobjectionable, as any ex-post adjustment will be detrimental to overall utility.

2.2 Defining Objectionable Option Sets

This then puts pressure on Olson’s second claim; whether or not the relevant option sets are objectionable. However, as she argues, in order to assess this, we must rise to her challenge of providing a matrix for objectionality. Well in this section, I will do so with an initially simple utilitarian answer: We will consider an option set objectionable, if its enforcing leads to counterfactually net lower utility. This is most clear in Olson’s Shift Worker case, in which the matter of primary importance is that the boss lowers the pay of the Tuesday workers for no good reason. In essence, he lowers Nina’s expected utility, without providing any positive utility in return. Notice, however, that as soon as we assert some good reason, (e.g. the work is harder on Wednesday than Tuesday, and by adjusting the pay he can better allocate labour) the more acceptable the enforcing of the option set becomes. This is because we have asserted some net positive utility that outweighs the negative. Therefore, we will consider an sub-optimal option set that leaves some utility ‘on the table’, as objectionable.

Olson also argues that we need a meta-account, of why we should accept a given account of objectionality, and I shall provide that too. My meta-account shall be of the Neo-Humean or Hobbesian variety. Such accounts start with the baseline assumption that we are rational agents that pursue interests, preferences or ends that are apparent to us, and as such, I argue that the endorsing of a maxim: ‘Enforced negative net-utility option sets are objectionable’, is likely a strategy that will lead to the forwarding of one’s own interests. It is this meta-account that explains why the Executor case strikes us as objectionable. What strikes us as objectionable is the fact that the executor, having divided the assets and being left with a remaining sum, splits up the cash with seemingly no good reason. As such, I put forth that when we consider this case, we ask ourselves: “Does it forward my interests to endorse the maxim that an executor in this situation ought to split up the remaining funds arbitrarily, with no good reason?”, and we find the answer to be no, we therefore find it objectionable, instead probably endorsing a maxim like “The remaining cash should be split 50/50”. Therefore, I propose that we are justified in endorsing the utilitarian account, because from a Neo-Humean position its universal acceptance is likely to lead to the forwarding of our interests.

One might remark that there is a disconnect in this account between the first level account, that ‘what determines an objectionable option set is net utility’, and the meta-account, ‘we are justified in endorsing the first-level account because it will forward our interests’. One might ask instead, if the neo-Humean story is true, why someone would not endorse the singular maxim ‘any option set that reduces my expected utility, is objectionable’.

I agree that at base, the Neo-Humean account implies this position, however, such a maxim is highly cognitively demanding, and non-cooperative. As a result, I argue, to limit deliberation costs, individuals may instead save time and maximise utility by endorsing the less demanding net-utility maxim. Whilst this strategy may come at short-term costs, it is plausible that over the long-term the decreased cognitive load, and increased cooperative abilities lead to this being the optimal maxim for a rational agent to endorse.

As such, we will consider an option set objectionable if it, from our perspective, deviates from the path of optimal net utility. Furthermore, we are justified in accepting this maxim as, from a Neo-Humean perspective, though it is a coarse-grained maxim, the increased coordinative abilities, and decreased cognitive load ought to lead to the furthering of our interests.

3. The Problem With Olson’s Second Claim

Given such considerations, and armed with a criteria of what makes option sets objectionable, we are now in a position to put pressure on Olson’s second claim, that we may have good reason to think that the relevant option sets are objectionable. In this section, I shall consider three ways in which the option sets for gender employment differences may be objectionable: Olson’s example of licensing, state interference and the market itself.

3.1 Licensing

Olson purports that the state, acting like the executor or boss, may have ‘put their thumb on the scale’ by using licensing laws in order to affect the supply, demand and remuneration of male-preferred and female-preferred occupations. Here, the charge seems to be the same as for the executor or boss, namely that the state has adjusted the option set for no good reason, and that the benefits of licensing are merely a ‘fringe benefit’ that workers ought not be entitled to keep. She does, however, say that this should be considered distinct from a Rawlsian justification, in which an increase in remuneration is necessary to induce further supply.

Olson’s characterisation of licensing’s effect on remuneration as any sort of ‘free lunch’ seems, to me, mistaken. Instead, all of licensing’s effect on remuneration occurs in a Rawlsian fashion. Let us observe the microeconomic implications of licensing laws. Licensing is a necessarily restrictive venture, its value arising specifically from excluding some members from an occupation that would otherwise be included if there was no licensing. As such, it necessarily decreases supply as a first order effect, which, if demand remains constant, means that equilibrium wages must rise in order to induce more people to ‘jump over’ the newly erected licensing hurdle. However, licensing may also have an effect on demand, through an increase in consumer confidence in the license holders. An increase in demand will encourage consumers to ‘bid more’ and thus, also increase the remuneration of the occupation. This has the upshot of meaning the wage-increasing effect of licensing is at no point a ‘free lunch’ or occurs in an arbitrary manner for no good reason, but arises in a strictly Rawlsian fashion as a result of the licensing’s restrictive effects on supply and its effect on consumer confidence.

To further demonstrate this point, let us imagine a nefarious government that wanted to increase the yearly take-home pay of a particular gender. Would licensing laws be an effective tool for them to accomplish this? I argue they would not. Let us say they scheme up a licensing law that applies to an occupation favoured by their target gender. This licensing law will necessarily be restrictive, and so, assuming demand remains constant, remuneration for that occupation will rise. Except, this will fail to accomplish the government’s goal, because even though the remuneration for the occupation may rise, due to the restrictive effect, there are now fewer members of their target gender employed in that occupation24. As a result, whilst the occupational remuneration is increased for those within the occupation, as demand remains the same, there are fewer members within the occupation receiving the benefits of such demand, and therefore the nefarious government fails its goal of aiding the gender as a whole. Let us even say that the government’s licensing elicits a positive effect on consumer confidence, and thus, demand rises. Depending on how high demand and remuneration rise, it is even possible that the equilibrium supply and remuneration of that occupation exceeds the previous equilibrium amount. Here it seems that the government may have succeeded in their task. However, I argue, the very fact that consumer confidence rose so much, indicates that there was a need for such licensing laws, in that they facilitated so many more people to make use of the service were they previously lacked the confidence to do so, and therefore increased net utility. As a result, the licensing, even though it does benefit the particular group, is not objectionable, because it is called for and increases net utility overall. Therefore, we should reject Olson’s arguments that the option set may be objectionable due to licensing. Licensing laws either fail to help a demographic, by lowering the number of a demographic that are employed in an occupation, though the remaining of them may experience a wage boost, or unobjectionably increases their aggregate remuneration through legitimate and utilitious rises in consumer confidence.

3.2 The State

Having argued against Olson’s specific example of the state making the option set objectionable through licensing laws, is it possible that the state may make the option set objectionable through other means? Certainly. Licensing laws are not the only avenue available to the state to affect the option set, and given we have defined ‘objectionable’ as a less-than-optimal net utility decision, it certainly seems plausible that the state may make suboptimal decisions. However, to take a leaf from Olson’s book, and simply reverse the burden-push, it is premature to consider a gender employment difference objectionable before this has been demonstrated.

Maximising net-utility, however, may not exhaust the story of the manners in which a state could make an option set objectionable. What if, in pursuing optimal net-utility decisions, the state inadvertently confers more of that utility on one demographic than another? Say, the state determines that the best move is to invest in education, increasing the demand and remuneration for teachers (71.6% women25) or to invest in manufacturing, increasing the demand for manufacturers (72.5% men26). What if this were to occur for the same group for five, ten, a hundred decisions in a row? This is objectionable, yet is in line with our previous definition of maximising net-utility, and therefore acts as a counterexample. As such, we must either attempt to accommodate this example, or reject our previous definition of objectionality.

Fortunately, we can revise our objectionality maxim, while remaining within a Neo-Humean framework. This is doable by arguing that the net-utility maxim is a coarse-grained strategy, whereas it is plausible that the optimal maxim for a rational agent to endorse is that ‘a state ought to make decisions which maximise net-utility, subject to some degree of balancing’. By balancing, I mean that after a certain amount of decisions in which a particular demographic does not benefit, or even loses, the state ought to deliberately make a non-optimal, though still net-positive decision that benefits that demographic. Endorsing a maxim with at least some balancing, acts as a sort of insurance, ensuring that, on the off-chance a long streak of optimal decisions does not favour an agent, they at least have guarantee their interests will be partially met. On the one hand, one might endorse zero balancing, accepting with faith that over time everyone’s utility will get a chance to benefit, or inversely might endorse maximal balancing, in which the utility of every government decision be tallied and distributed evenly. From a Neo-Humean perspective, the optimal balancing maxim to endorse for an individual will depend on their risk tolerance, and for a society, the aggregate risk-tolerance of its citizens. As such, we will consider a state as objectionably influencing option sets if they transgress by acting in a suboptimal manner regarding net-utility, or by violating an individually or societally held balancing maxim.

Such violations ought to be reasonably rare, at least in liberal democracies, which contain an inbuilt balancing mechanism through elections. According to a Downsian economic model of voter behaviour27, voters ‘spend’ their votes to buy ‘utility’ in the form of favourable policies. As such, unmet interests of demographics form political ‘alpha’ incentivising future politicians to meet those needs in exchange for votes. Objectionable option sets arising from state action, then, are certainly possible, but it remains the task of the critic of a particular gender employment difference to empirically demonstrate this case.

3.3 The Market

Are there other means an objectionable option set could arise, say, spontaneously through market forces? I think so, and in this section I consider just one form of this, in the form of feedback loops.

Feedback loops occur in which a suboptimal equilibrium is reached, which reinforces and continues to perpetuate itself, causing a particular system to become ‘stuck’. One example of this regarding gender employment differences is based on the following loop28:

a) Women are more likely than men to experience a human capital disruption due to child-raising. This leads to b)

b) Firms are incentivised to offer a higher wage to attract employees who are less likely to experience a human capital disruption, as they represent a less risky, higher return on investment to the firm. This leads to c)

c) A male and female couple seeking to maximise their utility while raising children will be incentivised to have the higher earner continue to work while the lower earner experiences a human capital disruption. This leads to a)

This situation is intuitively objectionable, but how can we rationalise this from a net-utility standpoint? It is difficult to spot an incorrect premise. I argue that it strikes us as objectionable because in b) there are female employees being offered a lower remuneration purely on the basis of their gender, who are not going to experience such a human capital disruption (e.g. they have already had, or will not have children). As such, the firms values them lower than their actual return on investment, which is objectionable in that it leaves potential utility on the table, leading to inefficiency and a higher cost of goods and services for all us.

A brief survey of remedies yields us three options. 1) Make it illegal to differentiate based on such signals. We might think this is unideal, as it forces companies to be split between the opposed incentives of maximising profit, and avoiding punishment, and will therefore incentivise the optimal strategy to be continuing to act on such information, but underhandedly. 2) Equalise the signals by enforcing a similar human capital disruption on the male side (e.g. enforced paternal leave29). We might think this, too, is unideal because it mandates a particular use of time in a coarse-grained manner, whereas families are likely to have a fine-grained preference split, thereby lowering net-utility. Finally, and the solution I propose appears optimal: 3) Allow those employees who would have been mispriced in virtue of an assumed human capital disruption, to counter-signal through contracts. This allows firms to mitigate their risk profile, and offer a wage-premium to those employees who were being mispriced, increasing net-utility. This approach is already used by many occupations which require a high investment of human capital to be viable, such as Australian Air Force Pilots, who have a required service period of service of 7-9 years after completing their training30. We ought to be careful, then, that any remedy to an objectionable option set addresses the base-level objectionality, improving the net-utility of the situation without introducing further downsides, and in this case, allowing for an increase of information and signals through contracts, does so.

As such, we ought to accept that objectionable option sets can arise in the form of feedback loops without any state intervention and simply by market forces. However, again to reverse Olson’s burden push, this falls to the critic of a gender employment difference to empirically demonstrate along with the fact that their championed remedy in fact improves net-utility, subject to any endorsed balancing maxims, and thereby resolves the objectionality.

4. Conclusion

This essay therefore concludes, having argued that whilst Olson’s specific argument regarding objectionable option sets as a result of licensing laws fails, it remains possible that an objectionable option set may arise, either through state intervention, or through the market itself. This position was reached by arguing that Olson’s first claim, ‘that mere choice does not render an outcome unobjectionable, if the relevant option set is objectionable’ was trivially true, and that this then put pressure on her second claim ‘that the relevant option set may be objectionable’. Her call for a criteria of objectionable option sets, as well as a meta-account of them was answered by a utilitarian criteria, in which we consider option sets to be objectionable if they are non-optimal from a net-utility standpoint. On a meta-level, from a Neo-Humean standpoint, accepting this maxim is likely to lead to the fulfilment of our interests, subject to further fine-grained maxims, such as balancing maxims. Regarding her second claim, I argued that her specific example of licensing laws fails, as it either results in fewer of a demographic being employed in that occupation, or it unobjectionably increases aggregate remuneration as the result of increased consumer confidence. While I argued that Olson’s specific example of an objectionable option set failed, it is still possible for an objectionable option set to arise both as the result of state intervention, and from the market itself. To take a leaf from Olson’s book, and to conclude, until the option set is empirically demonstrated to be objectionable in such a manner, it therefore remains premature to declare a gender employment difference objectionable as a result of it. If such a diagnosis were demonstrated, however, we should welcome it, and the increase in net-utility its addressing would bring.

Bibliography

“ADF Careers - Pilot, Period of Service.” https://www.adfcareers.gov.au/

jobs/job-details.

Barclay, Linda. “Liberal Daddy Quotas: Why Men Should Take Care of the Children, and How

Liberals Can Get Them to Do It.” Hypatia 28, no. 1 (2013): 163–78.

Calnitsky, David. “The High-Hanging Fruit of the Gender Revolution: A Model of Social

Reproduction and Social Change.” Sociological Theory 37, no. 1 (March 1, 2019): 35–61.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275119830448.

Cook, Cody, Rebecca Diamond, Jonathan V Hall, John A List, and Paul Oyer. “The Gender

Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers.” The

Review of Economic Studies 88, no. 5 (October 1, 2021): 2210–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/

restud/rdaa081.

Downs, Anthony. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political

Economy 65, no. 2 (1957): 135–50.

“Gender Indicators | Australian Bureau of Statistics,” https://www.abs.gov.au/

statistics/people/people-and-communities/gender-indicators.

“Gender Pay Gap Data | WGEA.” https://www.wgea.gov.au/pay-and-

gender/gender-pay-gap-data.

Goff, Sarah. “Discrimination and the Job Market.” In The Routledge Handbook of the Ethics of

Discrimination. Routledge, 2017.

Guest, Ross. “The Real Gender Pay Gap.” POLICY 34, no. 2 (2018): 3–7.

“Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, April 2024 | Australian Bureau of Statistics,”

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-

australia-detailed/latest-release .

Olson, Kristi A. “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?” Philosophical Topics 40, no. 1 (2012): 45–61.

“Solving Which Trilemma? The Many Interpretations of Equality, Pareto, and Freedom of

Occupational Choice.” Politics, Philosophy and Economics 16, no. 3 (2017): 282–307.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1470594x17704401.

Payscale - Salary Comparison, Salary Survey, Search Wages. “2024 Gender Pay Gap Report

(GPGR),” https://www.payscale.com/research-and-insights/gender-pay-

gap/.

SafeWorkAustralia.org. “Work-Related Fatalities | Safeworkaustralia,” 2024. https://

data.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/interactive-data/topic/work-related-fatalities.

Stergiou-Kita, Mary, Elizabeth Mansfield, Randy Bezo, Angela Colantonio, Enzo Garritano, Marc

Lafrance, John Lewko, et al. “Danger Zone: Men, Masculinity and Occupational Health and

Safety in High Risk Occupations.” Safety Science 80 (December 1, 2015): 213–20. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.029.

Footnotes

Kristi A. Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?,” Philosophical Topics 40, no. 1 (2012): 45 ↩

cf. Sarah C. Goff, “How to Trade Fairly in an Unjust Society: The Problem of Gender Discrimination in the Labor Market,” Social Theory and Practice 42, no. 3 (2016): 555 ↩

“Gender Indicators | Australian Bureau of Statistics,” 2023, https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/gender-indicators. ↩

“2024 Gender Pay Gap Report (GPGR),” Payscale.This presumes a similar result will be found in Australia. ↩

Cody Cook et al., “The Gender Earnings Gap in the Gig Economy: Evidence from over a Million Rideshare Drivers,” The Review of Economic Studies 88, no. 5 (October 1, 2021): 2212 ↩

cf. Ross Guest, who finds 4-8% in Ross Guest, “The Real Gender Pay Gap,” POLICY 34, no. 2 (2018): 4 ↩

“Median Weekly Cash Earning - Gender Indicators | Australian Bureau of Statistics,” May 2023 ↩

SafeWorkAustralia.org, “Work-Related Fatalities | safeworkaustralia.gov.au” and Mary Stergiou-Kita et al., “Danger Zone: Men, Masculinity and Occupational Health and Safety in High Risk Occupations,” Safety Science 80 (December 1, 2015): 213–20 ↩

“Gender Pay Gap Data | WGEA,” ↩

“Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, April 2024 | Australian Bureau of Statistics,” ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 45 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 47 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 48 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 48 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 49 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 49 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 51 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 51 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 54 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 51 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 52 ↩

Olson, “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?”, 52 ↩

cf. Olson’s account of internal vs. external equality in Kristi A. Olson, “Solving Which Trilemma? The Many Interpretations of Equality, Pareto, and Freedom of Occupational Choice,” Politics, Philosophy and Economics 16, no. 3 (2017): 287 ↩

Presuming an equal percentage of men and women are denied licensing. ↩

“Gender Indicators | Australian Bureau of Statistics.” ↩

“Gender Indicators | Australian Bureau of Statistics.” ↩

Anthony Downs, “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy,” Journal of Political Economy 65, no. 2 (1957): 137 ↩

cf. David Calnitsky, “The High-Hanging Fruit of the Gender Revolution: A Model of Social Reproduction and Social Change,” Sociological Theory 37, no. 1 (March 1, 2019): 48 ↩

Linda Barclay, “Liberal Daddy Quotas: Why Men Should Take Care of the Children, and How Liberals Can Get Them to Do It,” Hypatia 28, no. 1 (2013): 168 ↩

“ADF Careers - Pilot, Period of Service,” ↩